Consider this. At online finance and banking-type sites, "Your security is important to us." In addition to standard login-id and password, for quite some time they've been fond of using these additional "security questions that only you will know".

Back in the day, it was always one thing in particular: "Mother's maiden name?" Obviously, only you will know that, because it's not important for anything. Well... except that NOW it's important because it got used everywhere as a security question. So every bank I dealt with knows it because they required it for me to do business with them.

So now that's been basically dropped, and a whole slew of other security questions have popped up. "Mother's date of birth?" "Childhood pet's name?" "Where did you go on your honeymoon?" (These are are all actual examples.) Obviously good security questions because no one would want to know any of this trivia.

HEY SECURITY DUMBASS -- AS SOON AS YOU ASK THIS QUESTION IT BECOMES OF INTEREST TO AN ATTACKER, AND THEREFORE A SECURITY VULNERABILITY.

What really pisses me off is that over time, these financial and business sites are going to know every scrap of personal information about my life if this goes on. All my relatives' and friends' birthdays. Nicknames and pets, favorite books/ authors/ places I dream of vacationing, etc., etc., etc. Every time one becomes somewhat widespread, they have to switch to something even more esoteric and private.

Nowadays I'm running into multiple sites (that I've used in the past) that are refusing to allow me access unless I give them some new tidbits of "security question" information. The nice girls at my local bank see my distress and helpfully suggest "Just make something up!" Which has the disadvantages of (a) now I'm not going to remember it and need to write it down, and (b) the fine print of the terms-of-service demand honest and factual information, and while I'm sure the tellers at the bank don't mind, I'm equally sure that the corporate entity will be happy to crucify me over a transgression like that if we ever get into a dispute.

Fuck that.

2009-12-24

2009-12-11

Disk Icons

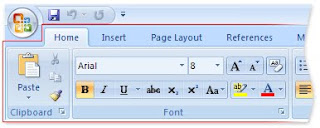

Something else that occurred to me teaching computers recently: Applications still use a picture of a floppy disk to indicate the "save" operation. (See the top of the MS Office Ribbon, in the last post.) This in an era when some of my college students have, apparently, never actually seen a floppy disk. I realized working with some of my students at the end of the semester that this icon doesn't have any intrinsic meaning to them. What to replace it with?

2009-11-14

MS Office Ribbons

So for the first time the computer literacy class I teach has been forced to switch over to MS Office 2007 products, and hence this past week I was finally forced to use the MS Office Ribbon interface. I tried to stay away from it, but now here it is finally. I really don't like it.

Here's the thing I really don't like about (aside from just the radical change from anything that's come before): It's semi-impossible to describe to someone else (say, a student) where they should be clicking.

In some sense, this is basically the primary disadvantage of the GUI having been doubled in intensity. With a command-line interface, it's easy to write out your instructions and transmit them in writing or verbally to another person. The GUI makes that piece of business a lot harder (now the geographic location that you're clicking on makes a big difference, and you wind up clumsily describing the pictures and icons that you're trying to activate).

So with the MS Office Ribbon, this is even more exacerbated. At least with the traditional menu bar, there was a linear order to each step of a process. Click on one menu item, another linear list drops down, find one item in that list, proceed to the next, etc. For example, to center the contents of a cell in Excel, I could provide a handout that says, "Click on: Format > Cells > Alignment > Horizontal > pick 'Center'". But now, I have to say something like "On the Home Tab, find the Alignment section, and kind of near the middle of that section there's a button that kind of has its lines centered, click on that". Very, very clumsy... and more so for lots of other examples that we can probably think of.

2009-10-08

Programming Project Idea

Here's a random class programming project idea. Everyone submits their name and a newly-made up password (not one that they use for anything else). Then, everyone writes a program to guess passwords, lets them run for an hour against the list, and sees how many matches they can make. Suggest a few strategies like a "brute force attack", a "dictionary attack" (providing a dictionary text file), guessing that some people use no numbers or caps (or all numbers), etc. Afterwards, analyze both successful attacks and the more secure passwords.

This would be more advanced than anything I've done in my classes, even though some of the programs could be relatively short. Interesting both for basic programming skill and insights on password security. Maybe seed the list with some instructor-made weak passwords as a baseline target.

This would be more advanced than anything I've done in my classes, even though some of the programs could be relatively short. Interesting both for basic programming skill and insights on password security. Maybe seed the list with some instructor-made weak passwords as a baseline target.

2009-07-29

Game Theory Lectures

I've been watching some Game Theory video lectures out of Yale University ( http://oyc.yale.edu/economics/game-theory ). It's a subject area I've been intrigued by for a while, so I was happy to see their availability online. Professor Ben Polak is an energetic and compelling presenter.

However, I keep being reminded that this is a course being given in Yale's Economics department. And I've long held a few very key critiques about the foundations of standard economic theory, that I feel make the entire enterprise miserably inaccurate. What I didn't expect is for these Game Theory lectures to feature a high-intensity spotlight directly on those shortcomings, in practically every single session.

Critique #1 is that economics deals only with money, and wipes out our capacity to deal with other values. Critique #2, probably more important, is that economics fatally depends on a “rational actor” assumption for all involved, which is simply not true. Let's consider them in order:

Critique #1: Economic theory is all about money, and the widespread use of the theory destroys our other values like family, community, craftsmanship, healthy living, emotional satisfaction, and good samaritanhood. As one wise man said, “They don't take these things down at the bank,” and therefore, they get obliterated when economic theory is put in play.

Now, Professor Polak makes a good, painstaking show in Session #1 of trying to fend off this criticism. “You need to know what you want,” he says, and runs an extended example wherein, if one player really was interested in the well-being of his partner in a game, well, that could be accounted for by assessing the value of those feelings, and adding/subtracting to the payoff-matrix appropriately, and then running the same Game Theory analysis on the new matrix, finally arriving in a different result. (Of course, along the way he also snidely refers to this caring player as an “indignant angel"). See? Game Theory can handle all kinds of different values, not just money.

But lets look later in the same lecture, where he has the students play the “two-thirds the average game” (more on that later). He holds up a $5 bill and says that the winner will receive this as a prize. Now – does he do the analysis of “what people want” (payoffs), which he just said was so keenly important? No, he does not. Only 15 minutes after this front-line defense, it goes forward without comment, that obviously the only value for anyone in the game is the money. So, even though we just lectured on how economic theory can handle different values, we immediately thereafter turn around and act out exactly the opposite assumption. Maybe some people want the $5... maybe some want to corrupt the results for their snotty know-it-all classmates... But no, we get it played out right before our eyes, immediately following the defense that “all values can be handled”, that as soon as money comes in the picture, in practice, we dispense of all other values and speak of nothing except for the cash money.

Critique #2: Economic theory presumes “rational players”, where all the people involved knowingly work to their own best interests all the time. Frankly, that's just downright absurd. People are routinely (1) uneducated or uninformed about what's best for themselves, (2) barred from receiving key information by more powerful institutions or interests, (3) obviously non-rational in instances of emotional stress, drug use, mental failures, and modern Christmas purchasing behavior, and (4) proven by cognitive brain science to be unable to correctly gauge simple probabilities and risk-versus-reward.

Now, consider lecture #1, where Professor Polak introduces game payoff matrices, and the idea of avoiding dominated strategies (that is, a strategy where some other available choice always works out better). With exceeding care, he transcribes each “Lesson” along the way onto the board, including this one: “Lesson #1: Do not play a strictly dominated strategy”. Okay, that's a reasonable recommendation.

But about 10 minutes later, he pulls a devious sleight-of-hand. Analyzing another game, he asks what strategy we should play. “Ah,” he says, “Notice that for our opponent strategy A is dominated, so you know they won't play that, they must instead play strategy B, and thus we can respond with strategy C.” Well, no, that reasoning about our opponent (the 2nd logical step here) is completely spurious; it only make sense if our opponent is actually following our lesson #1. But, have they taken a Game Theory class? Do they know about “dominated strategy” theory? Do they actually follow received lessons? None of those things are necessarily (or even likely, I'd argue) true.

In other words, he assumes that all players are equally well-informed and “rational”, which isn't supportable. And, this assumption is kept secret and hidden. It would even be one thing if Professor Polak came out and said “For the rest of our lectures, let's also assume that our opponents are following the same lessons we are,” but no, he quite scrupulously avoids calling attention to the key logical gap.

And he does is it again, even more outrageously, in Session #2, when analyzing the class' play of the “two-thirds the average game” (a group of people all guess a number from 1-100; take the average; the winner is whoever guessed 2/3 of that average). He has a spreadsheet of everyone's guesses in front of him. Speaking of guesses above 67 (2/3 of 100), he says, "These strategies are dominated – We know, from the very first lesson of the class last time, that no one should choose these strategies." Except that, as he points out mere seconds later, several people did play them! (4 people in the class had guesses over 67; this occurs 46 minutes into lecture #2.) Nontheless, he continues: "We've eliminated the possibility that anyone in the room is going to choose a strategy bigger than 67...". But how can you possibly contend that you've “eliminated the possibility” when you have hard data literally in your hand that that's simply not true? Answer: It's the “rational player” requirement of all economic theory, which demonstrably collapses into sand if the logical gap is recognized and/or refuted. This infected logic continues throughout the class; in sessions #3 and #4 he repeats the same goose-step in regard to "best response" (1:10 into lecture #4: "Player 1 has no incentive to play anything different... therefore he will not play anything different."), and so on and so forth.

However, I keep being reminded that this is a course being given in Yale's Economics department. And I've long held a few very key critiques about the foundations of standard economic theory, that I feel make the entire enterprise miserably inaccurate. What I didn't expect is for these Game Theory lectures to feature a high-intensity spotlight directly on those shortcomings, in practically every single session.

Critique #1 is that economics deals only with money, and wipes out our capacity to deal with other values. Critique #2, probably more important, is that economics fatally depends on a “rational actor” assumption for all involved, which is simply not true. Let's consider them in order:

Critique #1: Economic theory is all about money, and the widespread use of the theory destroys our other values like family, community, craftsmanship, healthy living, emotional satisfaction, and good samaritanhood. As one wise man said, “They don't take these things down at the bank,” and therefore, they get obliterated when economic theory is put in play.

Now, Professor Polak makes a good, painstaking show in Session #1 of trying to fend off this criticism. “You need to know what you want,” he says, and runs an extended example wherein, if one player really was interested in the well-being of his partner in a game, well, that could be accounted for by assessing the value of those feelings, and adding/subtracting to the payoff-matrix appropriately, and then running the same Game Theory analysis on the new matrix, finally arriving in a different result. (Of course, along the way he also snidely refers to this caring player as an “indignant angel"). See? Game Theory can handle all kinds of different values, not just money.

But lets look later in the same lecture, where he has the students play the “two-thirds the average game” (more on that later). He holds up a $5 bill and says that the winner will receive this as a prize. Now – does he do the analysis of “what people want” (payoffs), which he just said was so keenly important? No, he does not. Only 15 minutes after this front-line defense, it goes forward without comment, that obviously the only value for anyone in the game is the money. So, even though we just lectured on how economic theory can handle different values, we immediately thereafter turn around and act out exactly the opposite assumption. Maybe some people want the $5... maybe some want to corrupt the results for their snotty know-it-all classmates... But no, we get it played out right before our eyes, immediately following the defense that “all values can be handled”, that as soon as money comes in the picture, in practice, we dispense of all other values and speak of nothing except for the cash money.

Critique #2: Economic theory presumes “rational players”, where all the people involved knowingly work to their own best interests all the time. Frankly, that's just downright absurd. People are routinely (1) uneducated or uninformed about what's best for themselves, (2) barred from receiving key information by more powerful institutions or interests, (3) obviously non-rational in instances of emotional stress, drug use, mental failures, and modern Christmas purchasing behavior, and (4) proven by cognitive brain science to be unable to correctly gauge simple probabilities and risk-versus-reward.

Now, consider lecture #1, where Professor Polak introduces game payoff matrices, and the idea of avoiding dominated strategies (that is, a strategy where some other available choice always works out better). With exceeding care, he transcribes each “Lesson” along the way onto the board, including this one: “Lesson #1: Do not play a strictly dominated strategy”. Okay, that's a reasonable recommendation.

But about 10 minutes later, he pulls a devious sleight-of-hand. Analyzing another game, he asks what strategy we should play. “Ah,” he says, “Notice that for our opponent strategy A is dominated, so you know they won't play that, they must instead play strategy B, and thus we can respond with strategy C.” Well, no, that reasoning about our opponent (the 2nd logical step here) is completely spurious; it only make sense if our opponent is actually following our lesson #1. But, have they taken a Game Theory class? Do they know about “dominated strategy” theory? Do they actually follow received lessons? None of those things are necessarily (or even likely, I'd argue) true.

In other words, he assumes that all players are equally well-informed and “rational”, which isn't supportable. And, this assumption is kept secret and hidden. It would even be one thing if Professor Polak came out and said “For the rest of our lectures, let's also assume that our opponents are following the same lessons we are,” but no, he quite scrupulously avoids calling attention to the key logical gap.

And he does is it again, even more outrageously, in Session #2, when analyzing the class' play of the “two-thirds the average game” (a group of people all guess a number from 1-100; take the average; the winner is whoever guessed 2/3 of that average). He has a spreadsheet of everyone's guesses in front of him. Speaking of guesses above 67 (2/3 of 100), he says, "These strategies are dominated – We know, from the very first lesson of the class last time, that no one should choose these strategies." Except that, as he points out mere seconds later, several people did play them! (4 people in the class had guesses over 67; this occurs 46 minutes into lecture #2.) Nontheless, he continues: "We've eliminated the possibility that anyone in the room is going to choose a strategy bigger than 67...". But how can you possibly contend that you've “eliminated the possibility” when you have hard data literally in your hand that that's simply not true? Answer: It's the “rational player” requirement of all economic theory, which demonstrably collapses into sand if the logical gap is recognized and/or refuted. This infected logic continues throughout the class; in sessions #3 and #4 he repeats the same goose-step in regard to "best response" (1:10 into lecture #4: "Player 1 has no incentive to play anything different... therefore he will not play anything different."), and so on and so forth.

2009-07-27

Essay on Time Management

Here's a beautiful essay by Paul Graham called "Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule":

http://www.paulgraham.com/makersschedule.html

In brief -- Managers work in hour-long blocks through the day; great for meeting people and having a friendly chat. Makers, however (writers, artists, programmers, craftsmen) work in half-day blocks at the minimum. Interfacing the two -- e.g., managers calling an hour-long meeting at some random open slot in their schedule -- cause the makers to completely lose the in-depth concentration on a task they require. Call this "thrashing" or "interrupts" or "exceptions", if you like. This blows away a half or a full day of productive work when it happens.

Great observation, and it rings extremely true in my own experience. One of the reasons I'm so happy to be outside the corporate environment these days.

http://www.paulgraham.com/makersschedule.html

In brief -- Managers work in hour-long blocks through the day; great for meeting people and having a friendly chat. Makers, however (writers, artists, programmers, craftsmen) work in half-day blocks at the minimum. Interfacing the two -- e.g., managers calling an hour-long meeting at some random open slot in their schedule -- cause the makers to completely lose the in-depth concentration on a task they require. Call this "thrashing" or "interrupts" or "exceptions", if you like. This blows away a half or a full day of productive work when it happens.

Great observation, and it rings extremely true in my own experience. One of the reasons I'm so happy to be outside the corporate environment these days.

2009-06-05

Jury Selection

A few years ago I was hauled into jury duty in Boston, and somewhat disturbed to find that it's impossible for me to ever get selected onto a jury. As soon as you respond differently from all other jurors in the room on any question, you're out (in my case, I was the only one to say "no" to the question "do you agree that you have to follow legal directions from the judge?"). Then a few weeks back my girlfriend was hauled into the Brooklyn court building, and was likewise disturbed to discover the exact same thing (in her case, she was the only one in the room to stick to an answer of "no" in response to, "do you know when someone is lying to you?").

I was confused and mystified by this for a while. We put our heads together with my friend Collin, and I think we finally stumbled into an explanation.

The point is this: Everyone wants to avoid a hung jury (that is, a mistrial, forcing the court & lawyers to try the case all over again another time). The way a jury really works behind the scenes in a criminal trial is that you start with some yes-votes and some no-votes, and over the course of a day or so one side simply batters down the resistance of the other (often through insults and intimidation, as witnessed by another friend), until there is finally a unanimous vote. And who could possibly interrupt this process? You guessed it, the rare personality type who is willing to reject the mob mentality and stand out, disagreeing with everyone else in a crowded, public courtroom.

It seemed odd to me that when we disagreed with the rest of the pool like this, both the prosecution & defense got all jumpy with us about it. You would think (from an expected-value analysis) that if you asked a defense attorney the question, "Which would you rather have as a result of a trial: a conviction or a mistrial?", the answer would be "a mistrial" (since there's at least some probability that your client is found innocent in the next trial). But now I'm guessing that this fails to take into account the opportunity-cost to the attorney in their time; possibly they would actually, ultimately prefer the conviction, and be able to move to other more promising cases, rather than re-try a case which apparently is not a good cause in the first place. (This is similar to the well-known disconnect in incentives between a house seller and the broker working on a commission.) They're not making this loudly known, but I now suspect that avoiding a hung jury may be priority #1 for all the lawyers and judges in selecting a jury, even beyond winning the actual case. Therefore, the able-to-disagree-alone-with-a-room-full-of-people personalities have got to go.

For those of you who want to get out of jury duty, I therefore give a simple, completely foolproof and hassle-free procedure. There's absolutely nothing difficult about it and requires no creativity. Simply pick something, anything in the questions and disagree with everyone else, and you will be immediately released. If you're honest, in fact, it's practically impossible not to do this.

I was confused and mystified by this for a while. We put our heads together with my friend Collin, and I think we finally stumbled into an explanation.

The point is this: Everyone wants to avoid a hung jury (that is, a mistrial, forcing the court & lawyers to try the case all over again another time). The way a jury really works behind the scenes in a criminal trial is that you start with some yes-votes and some no-votes, and over the course of a day or so one side simply batters down the resistance of the other (often through insults and intimidation, as witnessed by another friend), until there is finally a unanimous vote. And who could possibly interrupt this process? You guessed it, the rare personality type who is willing to reject the mob mentality and stand out, disagreeing with everyone else in a crowded, public courtroom.

It seemed odd to me that when we disagreed with the rest of the pool like this, both the prosecution & defense got all jumpy with us about it. You would think (from an expected-value analysis) that if you asked a defense attorney the question, "Which would you rather have as a result of a trial: a conviction or a mistrial?", the answer would be "a mistrial" (since there's at least some probability that your client is found innocent in the next trial). But now I'm guessing that this fails to take into account the opportunity-cost to the attorney in their time; possibly they would actually, ultimately prefer the conviction, and be able to move to other more promising cases, rather than re-try a case which apparently is not a good cause in the first place. (This is similar to the well-known disconnect in incentives between a house seller and the broker working on a commission.) They're not making this loudly known, but I now suspect that avoiding a hung jury may be priority #1 for all the lawyers and judges in selecting a jury, even beyond winning the actual case. Therefore, the able-to-disagree-alone-with-a-room-full-of-people personalities have got to go.

For those of you who want to get out of jury duty, I therefore give a simple, completely foolproof and hassle-free procedure. There's absolutely nothing difficult about it and requires no creativity. Simply pick something, anything in the questions and disagree with everyone else, and you will be immediately released. If you're honest, in fact, it's practically impossible not to do this.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)